Imagine a device that lets you move heat very quickly from one place to another, yet needs no power, no electricity, no pumps, and no moving parts. You might think, “Sure, that’s what metals like copper or crystals like diamond are for, with diamond being the best on earth.” But what if you could move heat much, much faster?

A team of scientists at Syracuse University has found this amazing capability exists inside a device called an oscillating heat pipe (OHP), in which ordinary liquids like water can move heat very effectively. Scientists have been building OHPs for years, but it has been difficult to measure exactly how much heat the liquid itself can carry.

To address this issue, the team built an OHP with a glass mid-section and rigorous experimental controls, ensuring that all heat had to be carried across by the liquid alone. What surprised the researchers most was that the liquids didn’t just move heat well, they moved it better than the best solids on earth. And not just by a little bit – more than 150 times faster than copper, and even 20 times faster than diamond itself.

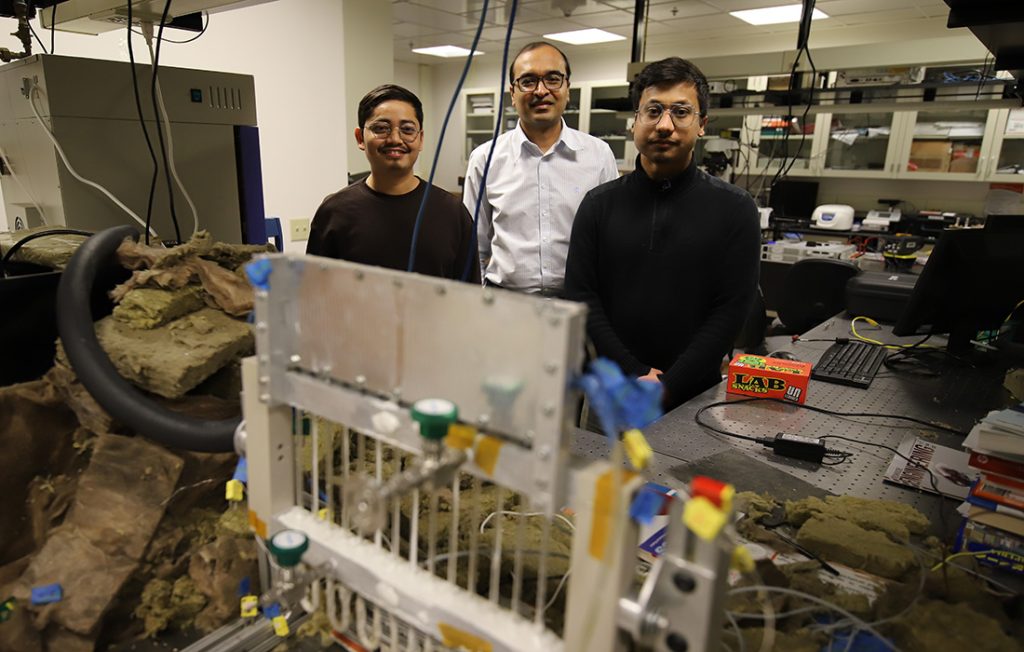

“With AI developing at a breathtaking pace, keeping electronics cool is essential – making it more important than ever to understand just how far the limits of heat transfer can be pushed,” explains doctoral student Ashok Thapa. Under the guidance of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Professor Shalabh C. Maroo in the College of Engineering and Computer Science, Thapa worked on the project alongside fellow doctoral students Maheswar Chaudhary and Ryan Gallagher. “We reported the highest liquid thermal conductivity ever measured inside an OHP,” says Thapa.

Maroo says this discovery means OHPs may be far more powerful than anyone realized. “By understanding how efficiently these liquids can oscillate and move heat across the device, we can now design better ways to cool phones, laptops, and future AI technologies at data centers without using extra energy.”

This research was recently published, with open (free) access, in Applied Thermal Engineering.